“In 1964, just four months before his sudden death in Berlin at the age of 36, Eric Dolphy recorded Out to Lunch!—an album that continues to rattle the walls of jazz orthodoxy. Released by Blue Note Records, it is the only album Dolphy made for the label, but it stands as one of the most important and uncompromising statements of the avant-garde jazz movement. Out to Lunch! is not merely ‘free jazz’ or post-bop abstraction. It is the blueprint for an entirely different approach to group interplay, improvisational space, and compositional structure.”

Title: Out to Lunch! But Right on Time — Eric Dolphy's Sonic Revolution Still Rings

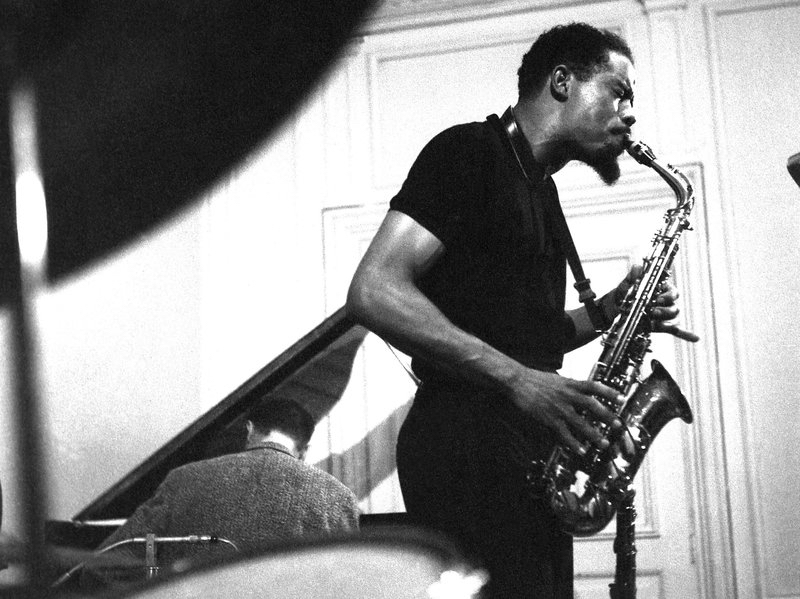

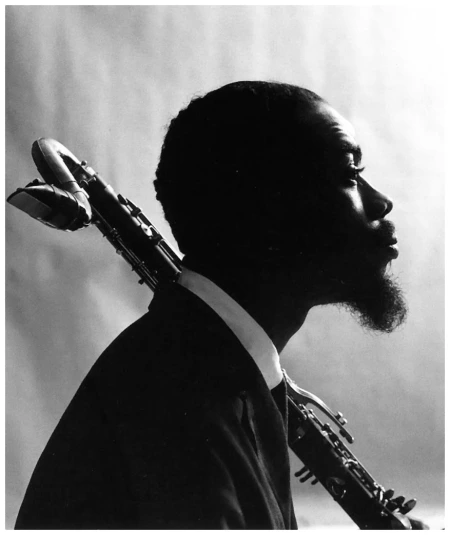

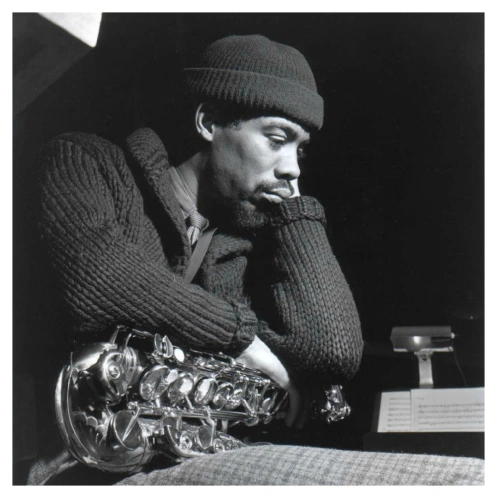

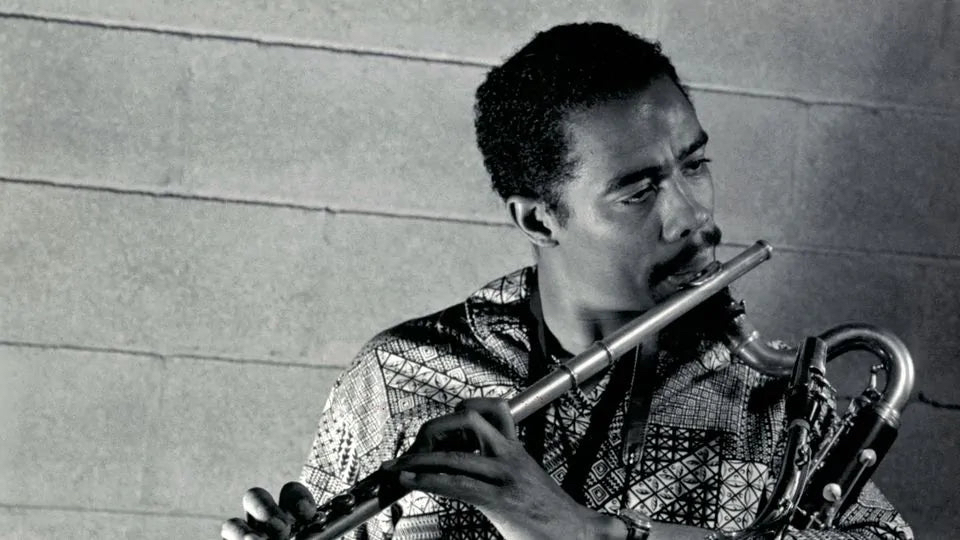

In early 1964, Eric Dolphy stepped into Rudy Van Gelder’s New Jersey studio carrying more than just a bass clarinet, flute, and alto saxophone. He brought with him a kind of restless insistence—that jazz must not sit still, must not conform, must not dim its light to match the room. What came out of those sessions was Out to Lunch!, an album that didn’t just stretch the boundaries of the genre—it scrambled them, rewrote them, made something entirely new. It’s a record that still sounds like the future, even now, sixty years after its release. And in a year when American jazz, and American life, were both teetering at the edge of upheaval, Dolphy offered something radical: not chaos, but order reimagined

In 1964, just four months before his sudden death in Berlin at the age of 36, Eric Dolphy recorded Out to Lunch!—an album that continues to rattle the walls of jazz orthodoxy. Released by Blue Note Records, it is the only album Dolphy made for the label, but it stands as one of the most important and uncompromising statements of the avant-garde jazz movement. Out to Lunch! It is not merely “free jazz” or post-bop abstraction. It is the blueprint for an entirely different approach to group interplay, improvisational space, and compositional structure.

From the first hit of the off-kilter vibraphone on “Hat and Beard,” Dolphy lets listeners know this is not about comfort. It’s about exploration. The tribute to Thelonious Monk is angular, halting, and strange in all the best ways. You don’t ease into this album—one drops right in. Dolphy’s bass clarinet lines snake through the air unpredictably. Bobby Hutcherson’s vibes don’t shimmer; they twitch. Freddie Hubbard plays against expectation. Richard Davis and Tony Williams move like dancers balancing on high-tension wires. It’s an ensemble built for tension and release, with no one player dominating for long.

There’s a duality to Dolphy’s playing throughout Out to Lunch!—precision in the chaos, clarity inside the swirl. Tracks like “Straight Up and Down” and “Out to Lunch” possess a satirical energy that borders on absurdity, yet they never descend into gimmickry. Dolphy’s command over his instruments—alto sax, bass clarinet, and flute—is complete, but he uses that mastery to expand the sonic conversation rather than centering himself within it.

Tony Williams, barely out of his teens, plays with the instincts of someone twice his age and with none of the caution. His drum work on the title track is a masterclass in controlled entropy. You can hear him nudging, prodding, and, at times, seemingly goading the ensemble to take another leap into the unknown.

It’s worth remembering that Dolphy emerged from the same West Coast scene that produced players like Buddy Collette and Charles Mingus. But whereas Mingus could be bombastic, Dolphy’s approach is surgical—he dismantles conventions from the inside out. His solos are not declarations but investigations.

Dolphy once said, “When you hear music, after it’s over, it’s gone in the air; you can never capture it again.” That sense of impermanence, of music as momentary truth, lives inside Out to Lunch!—a record that resists pinning down or

Thelonious Monk at the 1964 Monterey Jazz Festival ©Jim Marshallreductive thinking. Sixty years later, its ideas still feel unresolved, open-ended, and radically alive. It’s not just Dolphy’s masterpiece. It’s a call to action disguised as a day’s work.

For listeners who treat jazz as more than a backdrop, for those who understand it as conversation, confrontation, communion—Out to Lunch! It remains one of the most rewarding challenges in the canon. You don’t put it on to relax. You put it on to listen.

Track Breakdown

1. Hat and Beard

A tribute to Thelonious Monk, this opening track is as odd and brilliant as its namesake. With Dolphy’s bass clarinet and Hutcherson’s angular vibes creating a warped pulse, the piece feels like it’s constantly tripping forward—deliberately unsure of its next step. It’s the perfect handshake into the rest of the record: strange, bold, unapologetic.

2. Something Sweet, Something Tender

Dolphy’s bass clarinet is mournful and introspective here, with Richard Davis’ bowed bass offering a ghostly counterpoint. It’s a reminder that Dolphy could be lyrical without ever softening his edge. The tune feels like a private conversation overheard through a thin wall.

3. Gazzelloni

Named after flutist Julius Baker’s teacher, this track sees Dolphy on flute, darting and skittering with joy and mischief. The rhythm section holds its ground with a deceptively simple swing while Dolphy dances freely above it. It’s both a nod to classical influence and a burst of joyous rebellion.

4. Out to Lunch

The title track is Organized Chaos. Dolphy leads the charge with a commanding saxophone presence, while Tony Williams deconstructs and rebuilds time behind the kit. The melody feels like a broken music box wound down by mad geniuses. It teeters on the edge of total breakdown but always finds its way back home.

5. Straight Up and Down

Closing the album with a warped fanfare, this track feels celebratory and chaotic, as if the group is marching out of the studio backward, laughing. Hubbard’s trumpet and Dolphy’s saxophone chase each other through shifting meters while Hutcherson jabs rhythmically beneath. It’s comic and unsettling—perfectly Dolphy.

Sidebar: Collaborations with Coltrane and Mingus

Dolphy’s work with Charles Mingus helped define the edges of hard bop and the emerging avant-garde. On albums like Mingus at Antibes and Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus, Dolphy’s role was often that of the disruptor—offering commentary rather than compliance. He challenged Mingus in real-time, and Mingus respected him for it.

His time with John Coltrane, especially during the 1961 Village Vanguard sessions, showed a different side. The Dolphy–Coltrane pairing created a kind of dual-propulsion—Coltrane exploring the vertical dimension of harmonic complexity, Dolphy spiraling outward with tonal invention. Their live recordings remain some of the most daring group improvisations in jazz history.

1964: A Moment of Upheaval and Innovation

Eric Dolphy recorded the album “Out to Lunch ” in 1964. Specifically, the Out to Lunch album studio recording date is February 25, 1964. releasing August 1964. It was one of the tectonic shifts. “The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law on July 2, 1964, by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The act was a landmark piece of legislation that outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin,“(1) and The Beatles had landed in America. Malcolm X left the Nation of Islam. In jazz, the genre was undergoing an identity crisis, torn between commercial pressures and spiritual callings. Dolphy’s record didn’t answer any of those pressures. Instead, it broke free from them.

Blue Note had just begun experimenting more boldly with the avant-garde. Out to Lunch! landed alongside Andrew Hill’s Point of Departure and Jackie McLean’s Destination… Out! as part of the label’s most fearless period. Dolphy’s album became an emblem of what jazz could be when it refused to play it safe.

Dolphy’s Enduring Influence: Reflections from Today

“There’s something in Dolphy’s music that still unsettles you,” says saxophonist James Brandon Lewis. “Not because it’s angry or aggressive—but because it’s honest. He wasn’t trying to fit into a genre. He was trying to tell you what he saw.”

Young improvisers—from Shabaka Hutchings to Mary Halvorson—still cite Dolphy as a North Star. Not just for his technique but for his fearlessness. He was a technician, yes, but also a visionary. And in an era increasingly saturated by nostalgia, Out to Lunch! It serves as a reminder that jazz still has room to move forward.

As Dolphy said: “Music, after it’s over, is gone in the air.” And yet, somehow, this record still lingers. Still teaches. He still listens back.

(1) Thai, L. T. (2015). Social Representations of American History and Academic Engagement and Performance of African American Students. https://core.ac.uk/download/79648713.pdf

-

“He created intensity without relying on crescendos… His playing always felt urgent; he is entirely invested in the moment.”

— James Brandon Lewis, saxophonist & composer

-

“Out to Lunch was to New Thing jazz as The Sex Pistols’ debut was to punk… it’s the one that blew the doors wide open.”

— uDiscoverMusic, critic feature

-

“Out To Lunch is certainly Eric Dolphy’s most adventurous album and his most self‑consistent attempt at freedom within bop.”

— Brian Morton, The Wire

-

“None the less Dolphy shows his passion and unique style that would influence future players still to this day.”

— Trevor MacLaren, All About Jazz

-

“The organized mayhem starts with Dolphy’s tunes… Half a century later it still sounds crazy in a good way.”

— Kevin Whitehead, NPR

Further Listening Across the Jazz Spectrum

- 🎷 No Better Blues from Prof. Wynton Marsalis — Tradition remixed with clarity and force.

- 🎻 You're the One, Rhiannon Giddens Right Now — Roots music, time-traveled.

- 🌾 Joni Mitchell’s Jazz Hisses Over Summer Lawns — Art-pop meets post-bop reverie.

- 🎹 Well Now, Bobby Timmons—Come On! — Soul-jazz’s melodic architect comes alive.

🎼 In Memoriam: Eric Dolphy (1928–1964)

Eric Dolphy’s life was one of restless musical invention—pushing jazz into uncharted terrain with his bass clarinet, flute, and alto saxophone. But on June 29, 1964, while in Berlin on a European tour, that life was cut tragically short. He was only 36.

Dolphy collapsed while staying in Berlin, suffering from complications related to undiagnosed diabetes—a condition he reportedly didn’t know he had. His blood sugar had reached dangerous levels, and he fell into a diabetic coma, a severe and life-threatening medical emergency.

What followed has been a matter of enduring sorrow and controversy: according to several historical accounts, Dolphy’s symptoms were misinterpreted by authorities as drug-related—a tragically common bias faced by many Black American jazz musicians abroad. As a result, appropriate treatment was delayed, and by the time insulin was administered, he had already slipped into insulin shock.

Eric Dolphy died not from addiction, nor excess, but from a treatable medical condition misunderstood in the moment. His passing left a silence in jazz just as he was beginning to be fully heard—as a composer, as a bandleader, and as a visionary collaborator with Charles Mingus, John Coltrane, Booker Little, and so many others.

Though he is gone, Dolphy’s sound endures—disruptive, lyrical, and infinitely curious. And his story remains a cautionary one: about the cost of medical inequity, about the assumptions that kill, and about a genius gone too soon.